Most modern librarians will tell you this sterotype no longer exists.

I question if it ever did.

Looking back through history, I see librarians who traveled to remote, sometimes dangerous, locations to share books with people who had none. I see those who fought hard to start the first children's libraries. I see defenders against censorship who, at times, stood up to entire communities.

Last night I was looking at a thesaurus, trying to find just the right word to describe these pioneers. Courageous? Daring? Gritty? Plucky (no, that one in itself is a stereotype, usually followed by the word "little," as in "the plucky little librarian!") Then I happened upon the phrase "badass" and decided I'd make an exception to my blogging-policy of using only language suitable for the Disney Channel. According to some sources, badass behavior is tough, even extreme -- yet worthy of admiration.

"Badass" is a compliment.

And it describes the librarians who served on the 1946 Newbery committee and made what was probably the most daring selection in the entire history of that award -- up to and including today.

One of that year's Honor Books begins with an idyllic scene of typical California teenager Sue Ohara and her brother Kim arriving home from school on a Friday afternoon. A dog waits with wagging tail. There are cookies in the cookie jar and chitchat about the glee club and debate team. The next afternoon Kim mows the lawn and Sue mails Christmas presents to family and friends. Then comes Sunday and that day -- December 7, 1941 -- changes everything:

Sue herself felt suddenly shelterless in this icy storm. Here were she and Kim, American-born; as American as baseball -- ice cream cones -- swing music. No, as American as the Stars and Stripes. Here they were, American from their hearts out to their skins. But there skins were not American. Their skins were opaque, their hair was densely black, their eyes were ever so little slanted. And their names were Sumiko and Kimio.

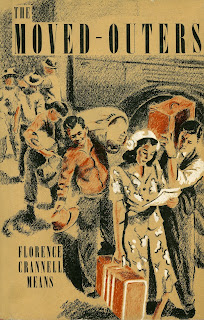

THE MOVED-OUTERS by Florence Crannell Means tells the story of these two Japanese-American teens as they and their family

are forced from their home and sent to relocation camps, first in California and later in Arizona. Novelist Florence Crannell Means was noted for writing books about minorities (RAFAEL AND CONSUELO, 1929; SHUTTERED WINDOWS, 1938) and this is one of her best. Living in the west, Ms. Means was able to personally visit the Amache Camp, where the fictional Oharas reside, as well as invite some interned young people into her own home. That up-close perspective on life in the relocation camps gave THE MOVED-OUTERS its detailed sense of authenticity. Against this vivid backdrop, the Oharas adjust to the hardships of encampment with an almost pioneering spirit, while Sue begins her first romance and the increasingly-bitter Kim flirts with the idea of joining a gang. Today you can find a number of great books for young readers on this sad chapter in American history, from memoirs (FAREWELL TO MANZANAR by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston) to novels (WEEDFLOWER by Cynthia Kadohata; BASEBALL SAVED US by Ken Mochizuki) to nonfiction (THE CHILDREN OF TOPAZ by Michael O. Tunnell and George W. Chilcoat), many which might be considered more genuine, historically accurate, or "politically correct" than THE MOVED-OUTERS. But the Means novel stands out as one of the earliest titles in this genre -- and, though purposeful, it's a compelling and heartfelt work. I find it remarkable that the book was published while the war was still ongoing --

are forced from their home and sent to relocation camps, first in California and later in Arizona. Novelist Florence Crannell Means was noted for writing books about minorities (RAFAEL AND CONSUELO, 1929; SHUTTERED WINDOWS, 1938) and this is one of her best. Living in the west, Ms. Means was able to personally visit the Amache Camp, where the fictional Oharas reside, as well as invite some interned young people into her own home. That up-close perspective on life in the relocation camps gave THE MOVED-OUTERS its detailed sense of authenticity. Against this vivid backdrop, the Oharas adjust to the hardships of encampment with an almost pioneering spirit, while Sue begins her first romance and the increasingly-bitter Kim flirts with the idea of joining a gang. Today you can find a number of great books for young readers on this sad chapter in American history, from memoirs (FAREWELL TO MANZANAR by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston) to novels (WEEDFLOWER by Cynthia Kadohata; BASEBALL SAVED US by Ken Mochizuki) to nonfiction (THE CHILDREN OF TOPAZ by Michael O. Tunnell and George W. Chilcoat), many which might be considered more genuine, historically accurate, or "politically correct" than THE MOVED-OUTERS. But the Means novel stands out as one of the earliest titles in this genre -- and, though purposeful, it's a compelling and heartfelt work. I find it remarkable that the book was published while the war was still ongoing --  and even more remarkable that it never feels like "wartime propaganda." THE MOVED-OUTERS neither defends nor criticizes the government's decision to intern American citizens, but instead focuses -- often heartbreakingly -- on the human consequences of this act. Kim builds a carrying case to bring the family's faithful old dog to the camp; when they learn that no pets are allowed, a decision is made and "the handsome carrying-case became Skippy's casket." An afternoon pass allows Sue and Kim to leave camp, but as they approach a drugstore to get an ice cream soda -- "just an American boy and girl like everyone else" -- they are confronted by a sign saying "NO JAPS WANTED HERE." When a relative is killed in the war, Kim tries to enlist in the service but learns "We're still classified enemy aliens." Even in the final pages of the novel, when Sue permanently leaves the camp and earnestly thinks, "O world, world! give us just a little chance. Let us be human. Let us prove that we are Americans," a nearby woman pulls away and "stares coldly" at the protagonist.

and even more remarkable that it never feels like "wartime propaganda." THE MOVED-OUTERS neither defends nor criticizes the government's decision to intern American citizens, but instead focuses -- often heartbreakingly -- on the human consequences of this act. Kim builds a carrying case to bring the family's faithful old dog to the camp; when they learn that no pets are allowed, a decision is made and "the handsome carrying-case became Skippy's casket." An afternoon pass allows Sue and Kim to leave camp, but as they approach a drugstore to get an ice cream soda -- "just an American boy and girl like everyone else" -- they are confronted by a sign saying "NO JAPS WANTED HERE." When a relative is killed in the war, Kim tries to enlist in the service but learns "We're still classified enemy aliens." Even in the final pages of the novel, when Sue permanently leaves the camp and earnestly thinks, "O world, world! give us just a little chance. Let us be human. Let us prove that we are Americans," a nearby woman pulls away and "stares coldly" at the protagonist.In a 1993 LIBRARY TRENDS article, Kay E. Vandergrift wrote, "The reception to The THE MOVED-OUTERS proved to be a mixed one. In spite of its literary awards, many schools and libraries did not purchase this book. Anti-Japanese feelings, even against the Nisei or those born and educated in this country, still ran high at its time of publication on February 28, 1945, especially on the West Coast where large numbers of Japanese Americans had been very successful prior to Pearl Harbor. There has always been the suspicion that it was, at least in part, personal greed and racial prejudice directed against these successful 'foreign-looking' immigrants which helped to fuel the negative feelings toward these citizens. When Japanese Americans were relocated, their property was often sold to others for less than its actual value. Those more sympathetic to the Nisei were often embarrassed by the actions of this country's War Relocation Authority and did not want to expose their shameful actions to young people. For these reasons, THE MOVED-OUTERS did not achieve the readership or visibility it deserved and was, for a long time, one of those Newbery Honor books available but not generally known by young people."

It's been over sixty years since THE MOVED-OUTERS was named a Newbery Honor (or "runner-up," as they were called in those days), taking its place beside that year's winner, STRAWBERRY GIRL by Lois Lenski. I don't know who served on the 1946 Newbery committee; I doubt any of the members are still alive. But re-reading the novel today, I'm amazed by what a brave choice those librarians made, picking a book about a controversial -- and, at that time, still very contemporary -- subject, knowing there could be a public outcry and that many libraries would not even purchase the novel.

...Yet if we were able to go back in time and praise these past librarians for their courage, I suspect they'd demure -- explaining that they were simply doing their job, selecting a well-written, thought-provoking, character-driven novel to honor -- and what's so brave about doing the right thing?

Yeah, but how many of us would have made the same type of decision in those tense wartime years? It's easy to laugh at the stereotyped librarian-figure but, in truth, those pioneers were really tough -- and truly worthy of admiration. They were badasses long before the word was invented.

3 comments:

These intelligent and unblinking people are truly deserving of this title as is the author herself.

A truly badass post -- thanks for this great site. I've enjoyed it many times before, so finally had to break through the wall and say so.

James Preller

I'm deeply pleased to see those badass librarians and Florence Crannell Means so beautifully acknowledged.

Post a Comment